by Lynn Whidden

Mythology,

contrary to popular usage, tells the believed sacred stories of a people. The

Dakota, one of the many groups of Siouan speakers, have a profound, detailed

mythology that explains the origins of all life; tells how a good life is

to be lived; and shows how to interact with the pantheon of supernatural

beings such as deceased humans, animals, birds and even inanimate objects. They

have an exclusive language, spoken only by the holy men, for discussion of

the sacred myths.

Mythology,

contrary to popular usage, tells the believed sacred stories of a people. The

Dakota, one of the many groups of Siouan speakers, have a profound, detailed

mythology that explains the origins of all life; tells how a good life is

to be lived; and shows how to interact with the pantheon of supernatural

beings such as deceased humans, animals, birds and even inanimate objects. They

have an exclusive language, spoken only by the holy men, for discussion of

the sacred myths.

Part of this secret language is dedicated to understanding

one of the greatest mysteries for humankind: the wind, thunder and lightning

that accompany it. For the  Dakota, and all dwellers of the northern plains,

the wind is omnipresent. The least movement of wind is readily felt because

the vastness of the grasslands is broken only by small stands of willow,

ash, cottonwood, poplar and the low shrubs that survive around sloughs and

creeks. Closer observation shows a landscape rich with the scent and colour

of plants such as astors, wild turnips (harvested by the Dakota), roses,

fireweed, mustard, sunflowers, and sweet clover.

Dakota, and all dwellers of the northern plains,

the wind is omnipresent. The least movement of wind is readily felt because

the vastness of the grasslands is broken only by small stands of willow,

ash, cottonwood, poplar and the low shrubs that survive around sloughs and

creeks. Closer observation shows a landscape rich with the scent and colour

of plants such as astors, wild turnips (harvested by the Dakota), roses,

fireweed, mustard, sunflowers, and sweet clover.

All of this provides a favourable habitat for the jackrabbit, weasel, fox, skunk, ground squirrel, badger, and before non-native settlement, for countless bison, antelope and deer.

The long, hot summers of the northern plains seem to slow the passage of time. Only the giant white clouds move, rolling overhead and casting shadows and flashes of sunshine on the land below. This is, however, the perfect condition for the creation of a variety of winds. By early afternoon, several whirlwinds may be travelling together. They are cone-shaped, circle in any direction, and although they may last only a few minutes, they have been seen to pick up jackrabbits. On the plains this type of day may culminate in a stirring electric storm, one of nature's most flamboyant shows. The clouds turn dark and the air comes alive. Thunder rumbles and gradually crescendos into resounding crashes, followed immediately by bolts of lightning, wind and finally rain.

Dakota

mythology shows us that they revered this magnificent natural force and,

at the same time worked with it as much as possible in everyday life. Dwelling

sites were carefully chosen and then the tipis erected, cleverly shaped to

stand impervious to the wind. Wind direction was carefully noted for tracking

animals and then used for drying the meat from the catch. And, of course,

the wind was a dryer for the hide clothing and especially the footwear. They

watched the wind fanning the great prairie fires that periodically renew

the terrain. They saw it shaping the ground surface, carrying away the light

soil, and sometimes making cultivation impossible.

Dakota

mythology shows us that they revered this magnificent natural force and,

at the same time worked with it as much as possible in everyday life. Dwelling

sites were carefully chosen and then the tipis erected, cleverly shaped to

stand impervious to the wind. Wind direction was carefully noted for tracking

animals and then used for drying the meat from the catch. And, of course,

the wind was a dryer for the hide clothing and especially the footwear. They

watched the wind fanning the great prairie fires that periodically renew

the terrain. They saw it shaping the ground surface, carrying away the light

soil, and sometimes making cultivation impossible.

The myth that deals with the winds centers around Tate, the Wind God. Tate was attracted to Ite, who, though not a goddess, lived at the entrance of the Spirit Trail. After the marriage Ite had four sons: the North, West, East and South winds.

When the first born, the North wind, became disobedient Tate took from him his first place and the wind order became West, North, East and South.

But Iktomi, the trickster, devised a plot to upset their ordered life. He encouraged Ite's vanity. She became obsessed with her beauty, flirted with the Sun, and neglected her Four Winds Song. Skan, the sky God, finally intervened. He decreed that Ite must return friendless to the world. Half of her beautiful face would become ugly and she would be known as double-faced woman. Moreover, she would give birth to an unusual child—Yumni, the whirlwind.

Tate would have to raise his five sons alone. Each day he sent them to travel the world. One day a beautiful woman appeared outside Tate's tipi. He welcomed her as a daughter and because she had an inexhaustible supply of food they knew she had supernatural powers. The four winds vied for her, but she chose Okaga, the South Wind; he folded his robe around her. As a present for the couple, the gods created the world and all that is in it.

As

we might expect, each of the winds had his own character. The four winds

are Wakan (not capable of being understood, spiritual). The wind that dwells

in the West is strong and good, and can protect humans from the harmful North

wind. The Thunderbird and the eagles live in the West and all the animals

were created there.

As

we might expect, each of the winds had his own character. The four winds

are Wakan (not capable of being understood, spiritual). The wind that dwells

in the West is strong and good, and can protect humans from the harmful North

wind. The Thunderbird and the eagles live in the West and all the animals

were created there.

Tate's second son, the North Wind, is strong, but cruel. He dresses in wolf furs and kills living beings without mercy.

The East wind is infrequently called upon; his major role is to bring dawn and with it a new day. But if Okaga, the warm South Wind, stays with you, you will have a pleasant life. He is the giver of life and kind to all. And finally, Yumni, the whirlwind knows all the games that are an important part of Dakota society.

Other forms of moving air were considered wakan. Smoke, air moving upwards, is central to communicaton. Those who smoked the pipe together were connected to each other and to the spirits of the deceased. Human breath is wakan. This makes the sound of flutes and of whistles extremely potent; only men are allowed to blow them. Flutes have power to captivate women of marriageable age as does the power of the whirlwind. In similar fashion, song travelling on the breath of the living being has power to carry thoughts and to heal. Song, like the wind, like human life itself, is always in the process of becoming and therefore is wakan. And the Dakota had many songs.

Noting

the functionality of natural shapes the Dakota imitated them in their human

constructions. Not only did the Dakota pray to the whirlwind before going

into a fight but also they attached cocoons to their shirts. This gave them

the quality of the whirlwind: they could not be controlled or predicted and

therefore confused the enemy. The cocoons were significant in other ways.

Noting

the functionality of natural shapes the Dakota imitated them in their human

constructions. Not only did the Dakota pray to the whirlwind before going

into a fight but also they attached cocoons to their shirts. This gave them

the quality of the whirlwind: they could not be controlled or predicted and

therefore confused the enemy. The cocoons were significant in other ways.

Moths and butterflies escaped from them and the movement of their wings was not unlike that of a whirlwind. One can only wonder about the personalities of individuals with names like "Blue Whirlwind" and "Whirlwind Bear!" An ancient ritual, the "yuwipi" also reflects the shapes and actions of whirlwinds, cocoons and moths. In this ritual a man is bound up in a quilt. His escape renews his strength just like the moth emerging from the cocoon.

Thus the plains environment is shaped directly by the wind and indirectly by the human transformation of culture to emulate wind qualities. All is interconnected. The tangible and intangible shapes and forces of nature are adopted by humans for their physical and spiritual needs.

Text:Lynn Whidden

Brandon University

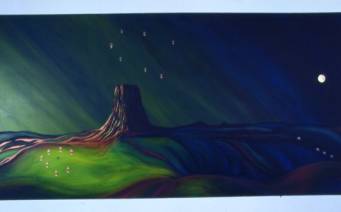

Images:

Colleen Cutschall

Brandon University

"Morning Prayer" Song:

Mike Hotain

Sioux Valley

Layout:

Richard Whidden

Armchair Airlines Computer Services, Inc.

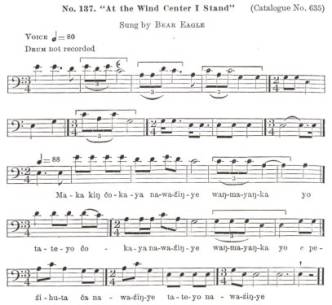

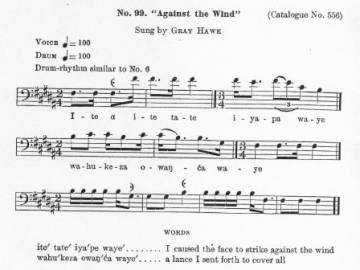

Frances Densmore. Teton Sioux Music. New York: Da Capo

Press, 1972

Royal B. Hasrick. The Sioux. Norman: University of Oaklahoma

Press, 1964.

William K. Powers. Sacred Language. Norman and London:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.

Colin Taylor. "Wakanyan: Symbols of Power and Ritual of

the Teton Sioux". Canadian Journal of Native Studies, Vol V11, Number 2,

1987.

James R. Walker. Lakota Belief and Ritual. Lincoln and

London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.